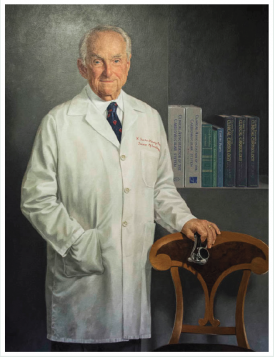

Biography of W. Proctor Harvey, MD

W. Proctor Harvey, MD

Director of the Division of Cardiology, 1950-1985

Watkins Proctor Harvey was born April 19, 1918, in Lynchburg, Virginia. He graduated from Duke University School of Medicine in 1943 and served in the Army Medical Corps in Europe during World War II.

In 1946, Dr. Harvey went to Harvard interning at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital under the legendary cardiologist Samuel A. Levine, becoming his first fellow, and collaborating with him in 1949 on the definitive textbook, “Clinical Auscultation of the Heart.”

Harold Jeghers, MD, former chief of the Boston University Medical Service at Boston City Hospital, who had been brought to Georgetown University as Chairman of Medicine to build a world-class academic medical center, recruited Dr. Harvey, who was then chief resident at Peter Bent Brigham, offering him the position of director of the Division of Cardiology. Harvey was impressed with Jeghers and accepted, despite the fact that there was no Division of Cardiology, and agreed to a salary so low that — in the words of Jack Stapleton, Harvey’s first fellow and later Dean of the School of Medicine — “It was the academic equivalent of the Alaska Purchase.”

Dr. Harvey not only created and built a division of cardiology from scratch, he established a cardiology fellowship program that became a model for programs at other teaching hospitals. His weekly teaching conferences, which featured amplified sounds of actual patients, became standing room only events attracting physicians from all over the nation and the world. His ability to reproduce heart sounds with his voice and by tapping his knuckles on a table often drew applause.

Dr. Harvey was unparalleled in the skill of clinical auscultation and in the art of physical diagnosis of cardiovascular disorders. He invented an improved stethoscope and innovated audiovisual approaches to teaching cardiology, and he served as President of the American Heart Association from 1969–1970. His books have been standard texts for more than 50 years, and his patients included at least four presidents as well as diplomats and members of Congress.

He was a proponent of direct examination of the patient as opposed to technological procedures and interventional tests such as cardiac catheterization. He maintained that “your ears are better than any test and don’t cost the patient a cent.”

Uniquely skilled in the art of medicine, unsurpassed in his knowledge of cardiology, and celebrated as a teacher, Dr. Harvey became one of Georgetown’s most valuable and enduring assets. His authentic concern for patients and their families along with his reassuring and considerate manner with them, which he learned emulating his mentor Levine and which he passed on to his hundreds of students, remain a legacy for medical education at Georgetown.

Dr. Harvey practiced what became known as the GT Ratio, maintaining that everyone should give more than they take. He held that at GTU, everyone’s GT Ratio should be greater than one. Said Don Knowlan, emeritus professor of medicine and a former Harvey Fellow, “Proctor Harvey’s GT ratio of course was infinite. All give, no take. He loved not to receive. All giving. His love was selfless. It was unconditional. It understood and accepted imperfections. He accepted us as we were, and yet each of us was a very special human being. He encouraged us to discover our own potential, our essential goodness, and develop it as we saw it, with his full support. His love extended to all human beings. It extended beyond the external, the superficial. It was directed to the well-being of others. It allowed you to love what was naturally unlovable, like marginal people, sick people, forlorn people. It was a love that was perfect for a physician devoted to the caring of the sick.”

David L. Pearle, a professor in Georgetown’s division of cardiology and a former Harvey Fellow said, “What Proc brought to Georgetown goes so far beyond the cardiology division. He affected the whole school as he was one of the leaders for so long that the humanity and warmth and sense of family he brought is still a part of the institution.”