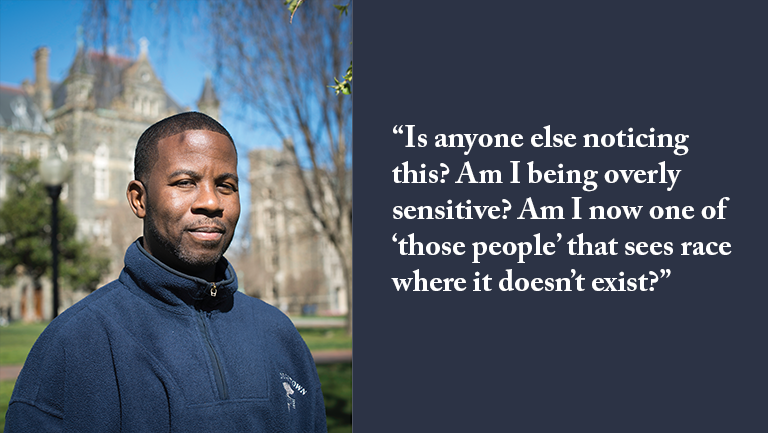

Story of Asante Dickson M.D.

Growing up in New York, I was exposed to some harsh life realities, many of which involved, were rooted in, or touched upon that artificial social construct we call race. Race has undoubtedly shaped my perception of myself. I have read many books describing physicians’ experiences in medicine, but am particularly drawn to the stories of physicians of color, because they offer understanding and comfort as I pursue my own medical career in this skin.

I am a proud graduate of Georgetown School of Medicine Class of 2000. I recall the student body not being particularly diverse, but I never felt disenfranchised or marginalized by my classmates. Within the preclinical curriculum however, race would rear its ugly head intermittently. One example that I remember vividly was a second-year lecture on sexually transmitted diseases. The lecturer discussed different diseases, their presentations, and treatments. But something had me attempting to disappear into the floor: all photos but one were of black patients.

I remember asking myself: “Is anyone else noticing this? Am I being overly sensitive? Am I now one of ‘those people’ that sees race where it doesn’t exist?”

I remember very little medicine from that lecture, but the repetitive photos of black men and women with horrible manifestations of sexually transmitted disease haunted me. In a room full of future doctors, the imagery conveyed the impression that STDs “belong” to black people, insinuating that black people are more sexually promiscuous than others. Now if black or other patients of color were also heavily represented in the hundreds of other lectures we had, then this would not have been such an outlying experience.

I decided that addressing it as a curriculum issue would be the best approach. I tracked down Dr. Princy Kumar, one of the school’s respected faculty members. As a physician of color herself, I hoped that she would understand my concern about the impact of this imagery in the classroom. I hoped that she would understand the danger of stereotyping patients in medical training, particularly in issues that tap into a longstanding historical, social, and/or behavioral narrative that stigmatizes people (often black men) as sexual deviants in need of control in order to keep society safe. Medical students are like sponges; they become the manifestation of a school’s teachings and culture.

Shaking her head in dismay as I explained my concern, Dr. Kumar simply said, “You are correct. And I will take care of this.”

Our individual biases—whether learned growing up or learned in medical training—and how we process them play a significant role in our effectiveness as physicians. Bias is within us all in some shape or form. The goal is to minimize the tendency for our biases to affect the egalitarian provision of health care.

I work in a medical system with two different patient populations. One caters to a middle and upper class clientele, the other to a largely immigrant and underserved population. The medicine practiced in both settings is slightly different as patients drive the culture in any medical system. When patients are part of the working poor, they come to medicine out of desperation. They feel grateful for any medical attention they receive as their lives outside of the hospital are in the shadows and in the forgotten corners of everyday life. Poorer patient populations will need patient advocacy more regularly from physicians. Patients in higher socioeconomic strata hold the healthcare system accountable. They are lucky enough not to have to worry about the cost of care or the lost income from the days out of work when family or they themselves are ill. On the other hand, the latter patient is more likely to receive unnecessary testing, imaging, and procedures. Physicians get pulled into a vortex of defensive practice in an effort to reduce the likelihood of missing a diagnosis or complications. What often follows is the inadvertent skyrocketing of healthcare costs and overutilization of resources.

I have always seen my Georgetown classmates as the best of the best. The professionalism and intelligence that they displayed throughout our training together left a lasting impression. I think that we need to make a more concerted effort as a Georgetown collective to address health care biases and disparities. We need to be more cognizant of the cultural and socioeconomic factors that challenge our intentions to heal. The increasing time and financial constraints placed on all of us in practice will make this goal even more challenging to achieve. Nonetheless, our Georgetown community must work towards addressing the real challenges of health care disparity, one health provider at a time.

Dr. Dickson is chair of radiology at Washington Adventist Hospital in Takoma Park, Maryland.