From Struggling Student to Medical Educator, Terao Shares Strategies for Success

Posted in News Stories | Tagged concept mapping, medical education, student support

(March 6, 2024) — A lot of medical students struggle with feelings of inadequacy and failure when trying to master everything thrown at them in their courses, said Michael Terao, MD, MEd. In fact, he almost gave up himself.

While studying at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Terao discovered a different learning methodology that helped him go from failing two-thirds of his first exams in anatomy and histology to earning good grades and becoming a sought-after tutor for his classmates.

As assistant dean for student learning in Georgetown University School of Medicine’s Office of Student Learning and Academic Advising (OSLAA), Terao strives to give students the strategies they need to succeed at Georgetown and beyond.

“In medical school, your grades don’t necessarily reflect effort,” Terao says. “They actually, at this level, often reflect methodology. Because I don’t think I’ve ever met a lazy medical student.”

A Map Forward

Terao bases this observation on his own experience. “What I remember most about that is I went to so many different places for help, worked so hard — and things just weren’t getting better,” he says.

Luckily, his school brought in a learning specialist, John W. Pelley, PhD, who showed Terao a different methodology for learning: concept mapping.

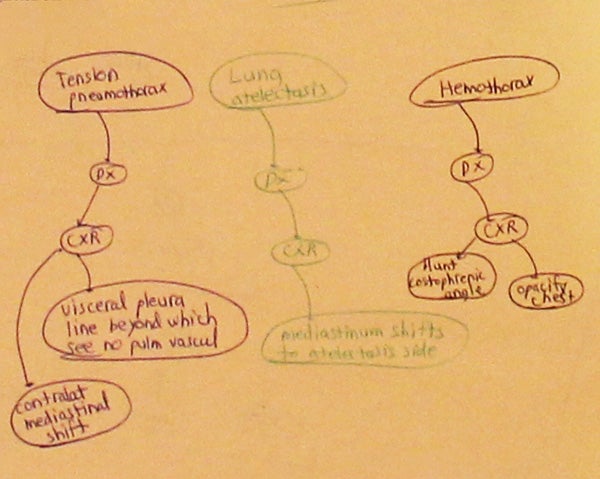

A concept map assists learners by assembling a crosslinked hierarchy that illustrates the relationships between elements in different parts of the map. It’s especially helpful for more visually oriented students, but can benefit any type of learner by making it easier to see how ideas connect into a bigger whole rather than trying to memorize every discrete piece of information.

“I was approaching the material as if I had to know everything with full mastery,” Terao says. That had worked in his academic career before medical school — as it does for many undergraduate students — because the content burden was light enough.

However, students often become overwhelmed by the content they need to learn in medical school. “Often, if you try to cover it all with complete mastery, you’re constantly falling behind and you can’t even retain what you’re learning in many cases,” he says.

For students like Terao, making a change to use a strategy like concept mapping can feel counterintuitive, because rather than doubling down, it involves doing a little less — but in a more targeted way. The change is especially hard for medical students, who tend to be perfectionists. “That’s how we got here,” he says. “And it hurts to say, ‘I’m not going to be perfect.’”

Concept mapping was a revelation for Terao. “My grades just skyrocketed, quite frankly, from failing to honestly doing better than the class average,” he says. “And without having to absolutely work myself to the bone. Just because the methodology was so effective.”

In his fourth year of medical school, Terao showed a couple of classmates what he’d learned using concept mapping. “Word just spread like wildfire throughout the student body that this stuff worked,” he says. “For the rest of fourth year, I was constantly getting students asking for consults from me.”

Terao trained seven students to keep the work going after he graduated and now, a decade later, a presentation on concept mapping is a mandatory part of orientation at Eastern Virginia Medical School.

While concept mapping was helpful for him, Terao emphasized that it’s not the right strategy for every student, and his goal is to customize his support to meet each student’s unique and individual needs. To that end, he’s assembled a library of learning strategies and made it available for free to members of Medical Education Learning Specialists, an organization that connects learning specialists nationwide.

‘That’s Where I Belong’

In addition to his work with OSLAA, Terao is a per-diem pediatric hematology-oncology hospitalist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. He was a sophomore English major at Allegheny College in Pennsylvania, with plans to become an English teacher and track coach at his old high school in Silver Spring, Maryland, when he was diagnosed with testicular cancer and had to undergo surgery and chemotherapy.

“It changed my career path,” he says. “I graduated as an English major, but planned to go to med school with that.”

Seeing the impact his illness had on his parents made Terao choose to go into pediatric hematology-oncology. “That really hit me hard and made me realize: Pediatrics, that’s where I belong,” he says. “I don’t know how these parents do it, where the cancer treatment lasts for weeks and months and even years. So it’s really important to help them through this.”

After medical school, Terao did his pediatric residency at University of California San Francisco’s Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, then served as chief resident in the Morehouse School of Medicine pediatric residency program in Atlanta, where he was named faculty member of the year.

Following a pediatric hematology-oncology fellowship at St. Jude’s, where he earned the 2019 American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Clinician Educator Award, Terao earned his master of education in the health professions from the Johns Hopkins University School of Education. He was hired in 2020 as a hematology-oncology physician at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital.

‘I’m That Guy’

Born near Osaka, Japan, Terao was adopted into an American family when he was just a few months old and grew up in the DC area around Georgetown and in Maryland. About a decade ago, he located his birth family on his mother’s side. Years later, he was contacted by the family of his biological father, who died and bequeathed a daikon farm in Japan to Terao. “I’m not sure what I’m going to do with it,” he admits. “It’s kind of a weird situation quite frankly.” (Daikon is a white root vegetable).

The farm may be one of the few places where Terao’s reputation as an expert on concept mapping did not precede him. Students from institutions around the country were seeking him out for consults, which he provided voluntarily after work hours.

One day, in his office at MedStar, as Terao took a call from yet another student asking for help, he heard his division chief, a nationally renowned cancer expert, in the office next door fielding calls from doctors all over the country seeking advice on difficult cases.

“Then it clicked with me,” he says. “Wait a second, I’m that guy who is getting contacted in med ed for these students. Why aren’t I focusing on this as a bigger part of my career?”

The realization prompted Terao to devote more of his time to helping future physicians. He worked as the preclinical content director at Sketchy for six months starting in June 2021. Then in March 2022, he started volunteering at Georgetown to support medical students’ learning needs while caring for patients at St. Jude’s.

“That volunteer work helped make it clear to me that this is really what I want to do with my life,” he says. But Terao also wanted to continue seeing patients, which led to the current arrangement when he was hired for the OSLAA position in February 2023. Today, three-quarters of his time is devoted to OSLAA, while he still works four shifts a month at St. Jude. Over the past year, OSLAA has performed 1,144 consultations via meetings and another 218 via email.

Recently, OSLAA hired another learning specialist, Mondel George, MD, MEd, MBA, putting it in an even better position to support medical students at Georgetown. “Hopefully that’ll help the office run even better than it does right now,” Terao says.

Michael von Glahn

GUMC Communications